Pacific Hitchhikers | The search for fish in the South Pacific

This story by Rob about our sailing trip was published in Anglers Journal this fall.

“Have you seen this fish?” I asked a young boy passing by on the rutted dirt road. My French was awkward and halting — I hadn’t used it in nearly a decade — but I took a guess and called it poisson-oisseux. As I showed him a small drwaing I had made with pencil and crayon, a gang of curious schoolkids on rusty pedal bikes quckly enveloped me. Apparently, tall, skinny white guys were an uncommon sight on Kauehi, a lazy tropical island in the Tuamotu Archipelago.

“Have you seen this fish?” I asked a young boy passing by on the rutted dirt road. My French was awkward and halting — I hadn’t used it in nearly a decade — but I took a guess and called it poisson-oisseux. As I showed him a small drwaing I had made with pencil and crayon, a gang of curious schoolkids on rusty pedal bikes quckly enveloped me. Apparently, tall, skinny white guys were an uncommon sight on Kauehi, a lazy tropical island in the Tuamotu Archipelago.

It was a crude picture of a bonefish, but I had no other means of gaining some local knowledge. No guides lived in the vicinity, and finding a tackle shop was out of the question. The kids fought over the drawing and exchanged perplexed murmurs until one of them exclaimed, “Oh, kio kio!” Jackpot.

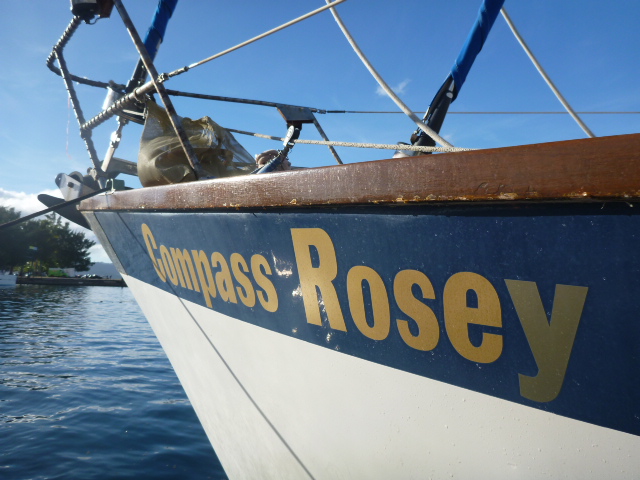

They pointed toward a small footpath and led the way as we snaked past barking dogs and overladen coconut trees. Finally, we arrived at an endless white flat dotted with turquoise pockets of deeper water. I smiled and started rigging my fly rod — I had traveled thousands of miles by sailboat to get here, and I wasn’t going to waste a moment.

They pointed toward a small footpath and led the way as we snaked past barking dogs and overladen coconut trees. Finally, we arrived at an endless white flat dotted with turquoise pockets of deeper water. I smiled and started rigging my fly rod — I had traveled thousands of miles by sailboat to get here, and I wasn’t going to waste a moment.

For years, I had longed to be part of the motley band of adventurers, dreamers and vagabonds who visited the South Pacific, from Capt. Cook to Gauguin. Sure, I wanted to cast from deserted white-sand beaches and enjoy the occasional cocktail over a sunset vista, but I had ambitions of more than just a one-off vacation. I was 37 and wanted to live by tidal shift and watch the rhythms of the sea unravel slowly, the way a river reveals its secrets to those who carefully cultivate it season by season.

Read the rest of the story as a PDF.

Read the rest of the story as a PDF.