‘Scanoodling’ Is Our New Favorite Water Activity

What is scanoodling?

It’s a word we made up that means dinking around in our motorized sailing canoe. Sometimes we paddle. Sometimes we sail. Sometimes we rev up the 3-horsepower motor.

The name comes from the type of canoe we bought this summer, a 16.5-foot Coleman Scanoe. It’s a flat-bottomed, aluminum-framed boat with a square back that’s durable and roomy — a cross between a skiff and a canoe.

Why we chose a scanoodle

Since we returned from our big trip across the sea, Rob and I have struggled to figure out the best boat to fit our lifestyle in Montana. As water-lovers, boats are vital for increasing our happiness factor.

We have two Alpaca Rafts, super-lightweight inflatable kayaks, which have served us well for short day trips or solo missions on rivers and wilderness lakes. But they’re too small for our family to undertake multi-day trips, and hell to paddle into the wind.

I used to share a 26-foot sailboat on Flathead Lake, but gave up that share when we set sail for the South Pacific. Since then, I’ve rented sailboats from friends for a few days at a time. But we missed the freedom of going sailing whenever I wanted. Plus, a traditional sailboat makes it tough to visit new places, since you’re either locked into one marina with dock fees or you need a big truck to tow a 5,000 to 10,000-pound yacht.

We looked high and low for good options, including small trimarans that our sedan could tow. Nothing seemed quite right.

Until we came across SailboatsToGo.com. This little company makes nifty sailing packages that attach to most kayaks or canoes. The whole kit weighs under 50 pounds, and can be checked as luggage on airplanes. We were sold, especially since we’re planning to sail through Florida’s Everglades National Park this winter.

We bought the sailing kit before we bought our own boat, and tested it out on friends’ canoes. Then we found the Scanoe, complete with a little outboard motor, for just $800. Packing up after work one Friday, we drove to Sandpoint, bought the Scanoe, and sailed to a remote beachside campsite on Lake Pend Oreille at sunset, the water like glass under our bow.

It was a match made in heaven.

Why we love scanoodling

- You can sail UP rivers, not just float down, which is uber-awesome.

- When there’s good wind, you can fill your sail instead of ruin your arms.

- And when the wind’s in your face and you can’t sail or paddle, the 3 hp outboard pushes the boat along at a good clip: ~8 mph without gear, ~5 mph fully loaded. One gallon of gas keeps us going over an hour.

- With the pontoons and leeboards (courtesy of SailboatsToGo) and the beamy, flat-bottomed canoe design, the boat is super safe. We can walk around inside or stand up to fish, and not worry that Talon might topple overboard.

- It’s a craft that can ply nearly any waterway in Montana. While I wouldn’t take it through Class III+ rapids or into the open ocean, the Scanoe does stay stable even when it takes on water.

- At 80 pounds, Rob and I can easily lift the Scanoodle on top of our car with the sail rolled up under the crossbars. The pontoons, leeboards and steering oar fit handily in the trunk. (Note: We’re planning to buy a small trailer to make transport even easier.)

- We can pack enough gear in the boat to stay out for a week and the three of us still fit comfortably.

- You never have to worry about running aground, since it’s made to be beached.

- Maintenance hours are negligible and dock fees are nonexistent.

Where we scanoodled this summer

- Missouri River – 50 miles over 5 days

- Lake Pend Oreille – 3 night camping trip

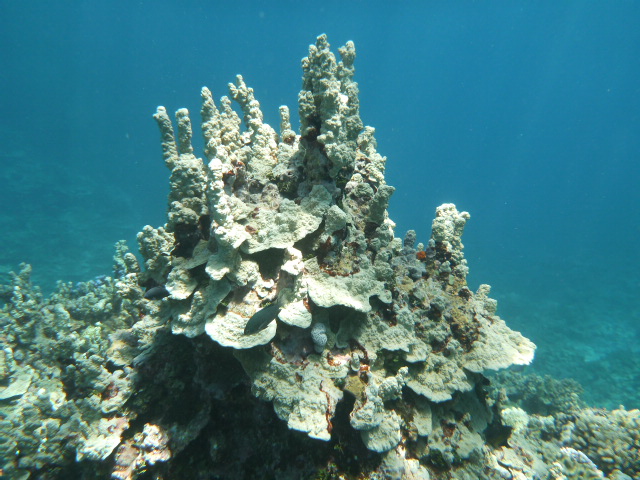

- Lake Upsata – a day of snorkeling and spearfishing

- Frenchtown Pond – where Talon caught his first fish

- Clark Fork River – afternoon floats near Missoula

- Cliff Lake – 2 night camping and fishing trip

- Flathead Lake – hour-long joy rides from Big Arm campground with friends and family

- Red Rock National Wildlife Refuge – across Upper Red Rock Lake and 2 miles up the Red Rock River

- Blanchard Lake & Clearwater River – after-work jaunts to spearfish and snorkel