The Secret to Getting the Best Compliment Ever

Traveling without internet is a recipe for one happy family.

Yesterday, a friend hugged me and said, “You look well-rested, Bri.”

I almost jumped with glee. “That’s the best compliment I’ve gotten in years!”

Because you know what well-rested means? Sanity. It means I don’t look like a cat dragged through the gutter after waking up every few hours to soothe a crying baby. And it means I don’t feel like a hummingbird dipping ever-so-briefly from one person, job, chore, event directly to the next.

The secret to my success at resting? Vacation. Actually, several of them. We were lucky enough to close out 2015 with a suite of trips, hitting the adventure trail with a vengeance during the holiday season. All told, we spent more than 3 of the past 5 weeks in a cabin, cabana, or tent. Most of those trips did not include wifi, a laptop, or even cell service, and all of them fell during the darkest days of the year. We went to bed early and stayed there late, connecting to each other instead of screens.

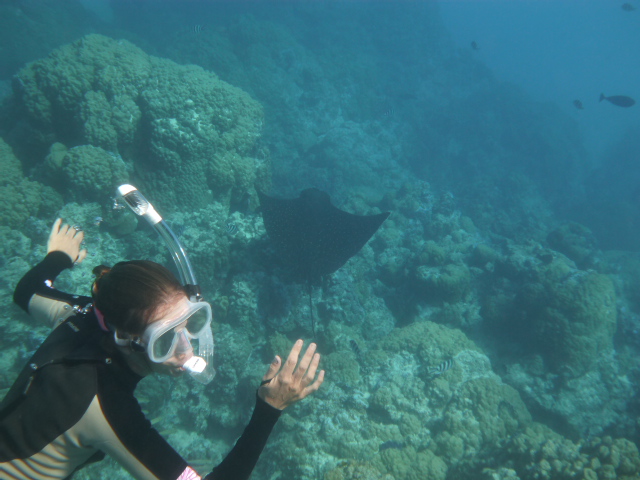

First up, we drove to northern Oregon to meet friends for the week of Thanksgiving, hiking in the Wallowa Mountains, saying hi to the Columbia River, and playing sort-of-in-tune music. A few days after returning home, Talon and Cassidy and I flew to Puerto Vallarta to explore a couple of remote villages in the southern stretch of Banderas Bay while Rob went on a fishing trip in the Everglades with old friends. And a week after that, we flew to Las Vegas, rented a car, and spent a week camping in Death Valley National Park with Mark and Katie.

As most parents know, traveling with a kiddo–especially an energetic, irrational toddler–isn’t exactly restful in and of itself. Just the opposite, in fact. We schlepped suitcases and sleeping bags, backpacks and carseats through jungles, deserts, oceans, and mountains. We endured way-below-freezing temperatures in a drafty tent, muddy river crossings after tropical rains washed out bridges, and shitty winter driving conditions over several mountain passes.

We consoled Talon when he woke up (often) in the middle of the night, uncomfortable because 10 people were crammed into a noisy cabin, mosquitoes were biting his head in Mexico, or an icy wind was howling across the desert.

But in the end, the challenges of navigating new places brought us closer as a family. It was well worth the work to watch Talon’s eyes light up at the sight of the sea, to hear his squeals of delight at the birds flying overhead, and to see his pride in climbing a sand dune all alone.

Moving beyond our daily Missoula routine gave me the space to breathe more deeply, and to focus inward long enough to rest easily while awake and asleep. I finally feel like my head and my heart are back in the same groove. Now, the trick is keeping them humming along in unified tempo back in the world of internet and errands. I’ll know I succeed if more people give me that ultimate compliment: that I look well-rested.

How’s that for a New Year’s Resolution? Happy 2016, friends!