Another Sabbath in Tonga

Behind our house chimes four-part harmony, 200 voices singing strong. Just one block away, another choir belts out a resonating song that rides through the steamy tropical air. Bells are tolling, and drums are beating. It’s 7:00 AM. Even though Rob and I don’t attend church, it sometimes feels like we do, simply through osmosis.

It’s Sunday in Neiafu, a day full of singing at church … and not much else. Tonga is an incredibly religious place, full of a variety of Christian derivates. You know how Seattle has a Starbucks on every corner? Well, Neiafu has more churches than Seattle has coffee shops. Luckily, the music that the Tongans belt out beats any elevator muzak you hear in coffee shops.

The sacred Sunday has been a theme throughout the Pacific islands we’ve visited. Towns are deserted, and visitors have to fend for themselves. Another unifying theme is the music — the Polynesians seem to have a harmonizing gene that skips most white folks. It’s impressive. Here in Tonga, they go to church twice on Sundays, and once almost every other day of the week. We don’t need an alarm clock here, since the church bells toll at 6am to wake up the congregation, 6:30am to make sure they’re getting dressed, and at 7am to signal the start of the service. Then they start beating drums. Loudly. We believe it’s to announce the entrance of the pastor/minister/reverend, but can’t say for sure (seeing as how we haven’t officially attended service yet).

Sundays are pretty slow around here. It’s against the law to go swimming, taboo to show your shoulders, and frowned upon if you do anything besides go to church and eat with your family. All shops and stores are closed and the main street looks like a ghost town. The Tongan constitution actually states that “The Sabbath Day shall be kept holy in Tonga and no person shall practice his trade or profession or conduct any commercial undertaking on the Sabbath Day.” Bakeries are granted a special exception and open at 4:00 PM, since bread is obviously a gift from God.

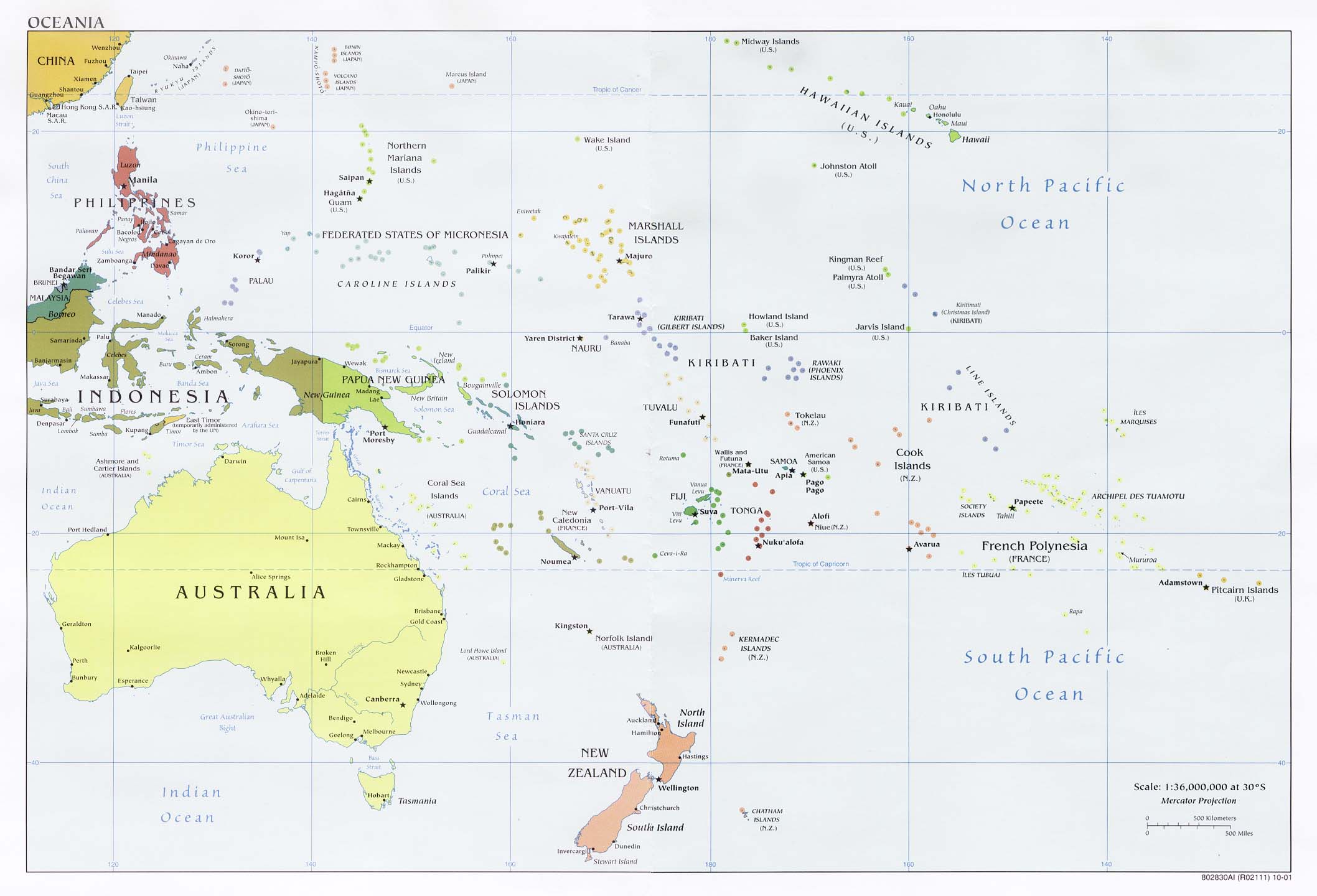

The Kingdom of Tonga, along with Fiji and Samoa, were settled around 3,500 years ago by brave seafarers from western lands. These islands served as the gateway for settlement of the rest of the Pacific islands — they are the heart of Polynesian culture. Then came the Europeans in the mid-1600s, who spread Christianity like a blanket over Tongan culture and customs (and over the bare breasts and shoulders of the people, too). The constitution quoted above was written in 1875, almost 100 years after the first missionaries arrived in Tongatapu. And the missionaries just kept on comin’ — Christianity spread rapidly in the Kingdom, integrating into almost every aspect of Tongan life.

We’ll get to a church one of these Sundays, as it seems imperative to understanding and appreciating the culture we’ve chosen to live in for the next few months. Meanwhile, we’ll enjoy the church bells from the comfort of our bed, and observe the Sabbath in our own style as we wander the empty streets of Vava’u.