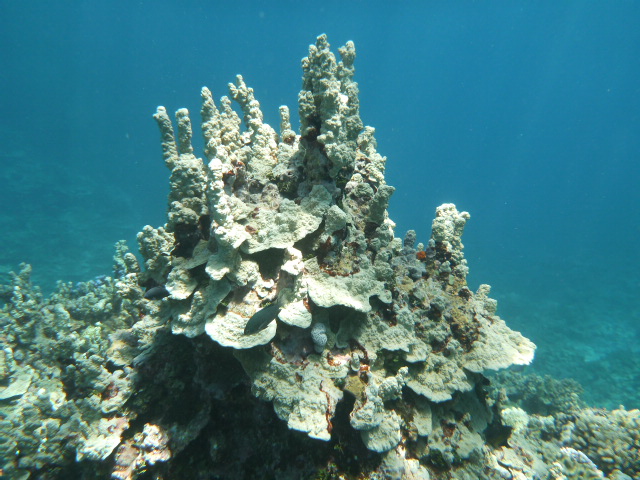

Top 10 Photos of the South Pacific

As we leave the Pacific for Southeast Asia, it seems like a good time to reflect upon what we’ve seen this past year. Here are a few of our favorite photos, which give a taste of sailing, swimming and living across the South Pacific islands. Note: This Top 10 album is also available on our Facebook page.

[anything_slider title=”Top 10 Photos of the South Pacific” column=”full-width” autoslide=”2″ slider_id=”3667″/]