Speaking the Native Tongue: Tongan and Malagasy

We’ve been in Tonga now for about two weeks, in the northernmost island group called Vava’u. I think we might stay a while, make a few friends, learn about the culture and generally just try to sink in a bit. Its something we have not had the chance to do so far on this trip, because we’ve moved fairly quickly. I’ll admit that I haven’t had much motivation to learn any new languages so far, for many reasons (laziness being one). But also, many of the native languages — like in French Polynesia — are in the process of being lost, or in some cases, marginally resurrected like in the Marquesas. French is taught in schools and widely spoken, even among locals. It was a great opportunity for me to work on the French that I learned in college and reinforced in Madagascar, where French is the second language.

Another language I learned in Madagascar is Malagasy, the native tongue. While French is spoken throughout most of the country, Malagasy is the day to day language and essential to learn if you want to work or travel in anywhere but the biggest cities. For me, learning Malagasy was the key into a secret culture, a whole new world of customs, activities and, frankly, a completely different way of looking at the world. Sure, French is a different language, but it has similar grammar patterns to English and sounds somewhat familiar to any speaker of a Romane language (Spanish, French, etc). But knowing Malagasy was like having a stamp of authenticity. A few well spoken words were all I needed to make a smile, get an invitation into someone’s home or, on certain days, entry into some ritual, rite or ceremony that was surely going to blow my mind.

Speaking Malagasy is quite different. For example: subjects come at the end of the sentence, and the passive voice is very common in expressions. The pronunciation is altogether different (my Malagasy friends would hold their noses and talk to imitate English speakers), and direct translations from English can be extremely difficult. I had to turn my mind upside down and inside out to really understand and to speak it like a native, but eventually I began to speak without thinking first. I even began to dream in Malagasy and on rare occasions, I still do.

So what’s this have to do with Tonga? One of the things I do in almost any country I visit is try to learn some basic phrases: hi, how are you, etc. If I have time and want to go deeper, I’ll then move on to some of the most commonly used verbs (have, want, etc) and then the numbers. Tongans speak English, but only to foreigners. As I listened toTongan on the street during our first few days, it sounded familiar to me and, walking around town, I felt instantly more at home then I have since leaving Missoula. The Tongan language has lots of vowels, and they often use what is called a glottal stop, kind of a staccato type effect. Think of a weak stutter or a mild cough between words. I felt like I had heard this language before.

But it was the numbers that really got me. And here’s why: below I have listed the Tongan numbers on the left and the Malagasy numbers on the right (as I know them from the region I lived).

1. taha iray

2. oa roa

3. tolu telo

4. fa efa

5. nima dimy

6. ono eni

7. fitu fito

8. valu valo

9. hiva sivy

10. tongofulu folo

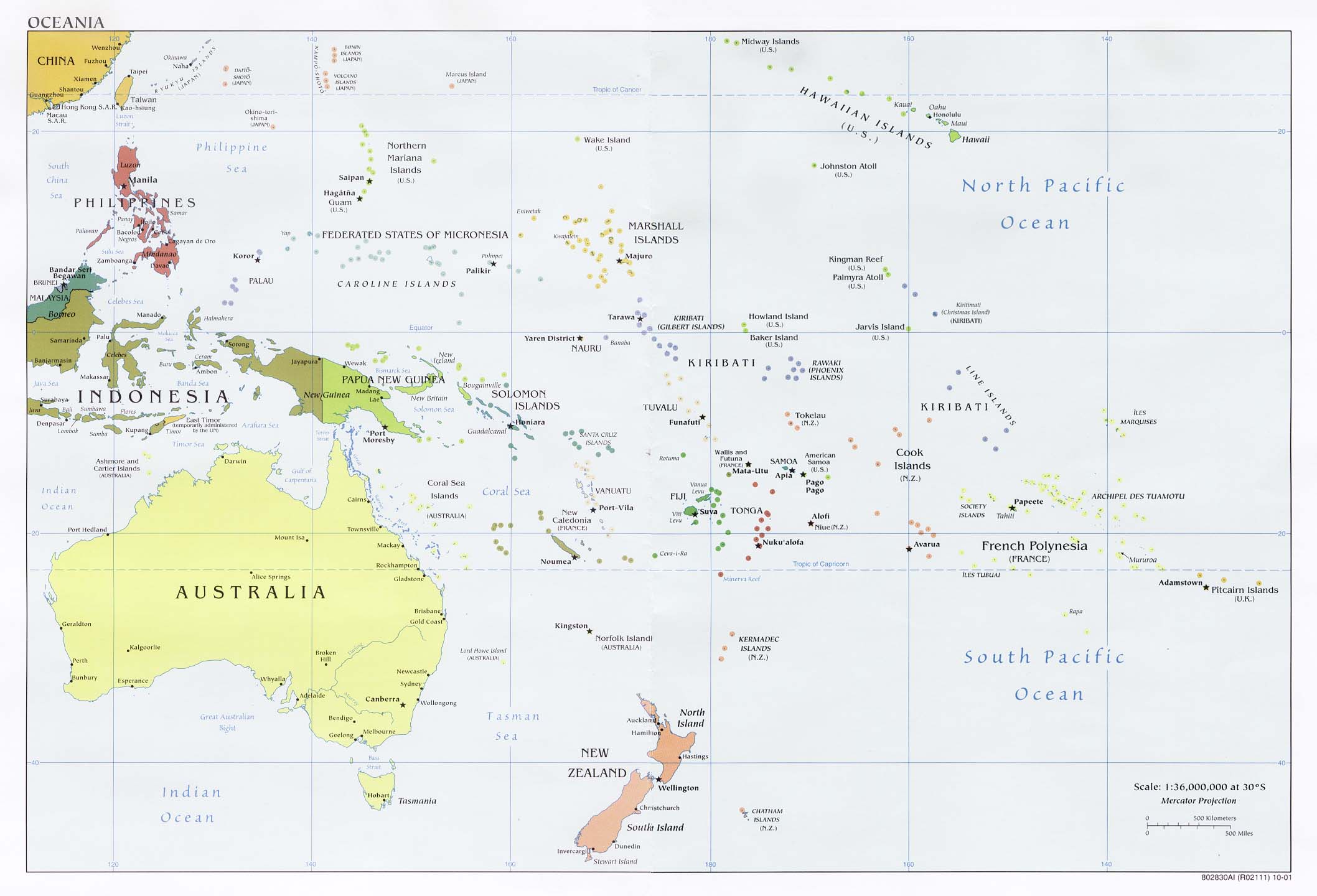

At first I was shocked. On paper, they look very similar. In pronunciation, they sound remarkably alike. The numbers for 7 and 8 sound identical (pronounced fee-too and vahl-oo). As I learned more, the similarities continued. The word for year is ta’u in Tongan and tao in Malagasy, and so on. I’ll admit that the two languages have less in common than not, but I’m still intrigued by the fact that they are even close. I had known that Malagasy was more like Indonesian than many of the languages in eastern Africa, which are geographically closer. Its one of the reasons I’ve always wanted to get to Indonesia on this trip. But upon further research (with some shoddy internet connections here in Nei’afu), I did a little research Tongan and Malagasy are actually part of the same language family, called the Malayo-Polynesian family, which extends from western Polynesia on through the Indian Ocean (mostly centered around the equator). Malagasy is considered to be the westernmost extent of this group and takes its base from dialects in the southeast corner of Borneo.

The people I lived with in Madagascar along the southwest coast were the Vezo: the sailors, the seafaring people who apparently travelled from Indonesia through the Indian Ocean, by the Middle East, along the coast of Africa and eventually over to Madagascar. Along the way, they picked up a little Arabic, a little Swahili, a little Bantu, and later on, a little French and English. The ancestors of the Tongans must have travelled in the opposite direction, and now here I am — another oceangoing nomad, looking for that promised land and grabbing a few kernels of language on the way.

This was my fourth consecutive performance at Off the Rack, dancing alongside Gillian and other talented teachers from the

This was my fourth consecutive performance at Off the Rack, dancing alongside Gillian and other talented teachers from the

My boss, Karen, likes to say that Missoula, Montana is the center of the universe. It’s certainly been

My boss, Karen, likes to say that Missoula, Montana is the center of the universe. It’s certainly been  We choose to live here for many reasons, but the main one is this: community. If Missoula is the center of the universe, then community is the center of Missoula. It’s the reason we make less money, endure long (really long) winters, and smoky summers. It’s the reason amazing, unexpected things unfold in the valley. It’s the reason we’re not selling our house when we leave for our adventures. It’s the reason

We choose to live here for many reasons, but the main one is this: community. If Missoula is the center of the universe, then community is the center of Missoula. It’s the reason we make less money, endure long (really long) winters, and smoky summers. It’s the reason amazing, unexpected things unfold in the valley. It’s the reason we’re not selling our house when we leave for our adventures. It’s the reason  And, most importantly, EVST and its people form the center of my Missoula community.

And, most importantly, EVST and its people form the center of my Missoula community.

A fellow Montanan — and friend of our friends —

A fellow Montanan — and friend of our friends —

It’s 2013 today. Christmas came and went, and so did the Winter Solstice. The days are already getting longer and lighter, pulling Montana toward spring.

It’s 2013 today. Christmas came and went, and so did the Winter Solstice. The days are already getting longer and lighter, pulling Montana toward spring.